Occasionally, I see a new artwork posted by an artist on social media which has a social commentary or political aspect to it. It’s not violent, obscene, or profane; the reference may be as obvious as a political cartoon, or so subtle that you have to think about it to get the message. The artwork may be a departure from the artist’s usual subjects or style. Regardless, viewers are quick to comment. Some compliment the artist on the work and the message. Others are offended and go on the attack; they may go so far as to swear they’ll never speak well of the artist again. This is not unexpected when you “put yourself out there”.

What amuses me is when an attacker says to the artist something like “Go back to painting pretty pictures and stay away from politics. Politics doesn’t belong in art.” Nothing says “I don’t know anything about art” like saying “Politics doesn’t belong in art.”

History is full of famous and not-as-famous artworks that embody political or social statements, literally and/or symbolically. You probably recognize some of these artworks, but if you’ve never read about them in historical context, you may not realize how controversial they were in their day, and that they probably resulted in threats to the artist. Here are just a few examples.

Peanuts, Charles Schulz, 1968

Who doesn’t love Peanuts? Cartoonist Charles Schulz was asked by a schoolteacher to introduce a Black character in 1968, days after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., as a way to positively influence attitudes about race. Guess what? He told her he’d wanted to for some time but he was afraid of seeming patronizing. So she corresponded further with him until he was ready. Franklin debuted as a regular Peanuts character later that year. Schulz was accused by the cartoon syndicate of adding Franklin for political effect, and many newspapers threatened to cancel Peanuts over it. He told the head of the syndicate “Either you print it as I draw it, or I quit.” Due to Peanuts‘ popularity, they relented. That wasn’t the end of the criticism he received about Franklin via letters, though, even though he also received a lot of positive letters. Read more about it here.

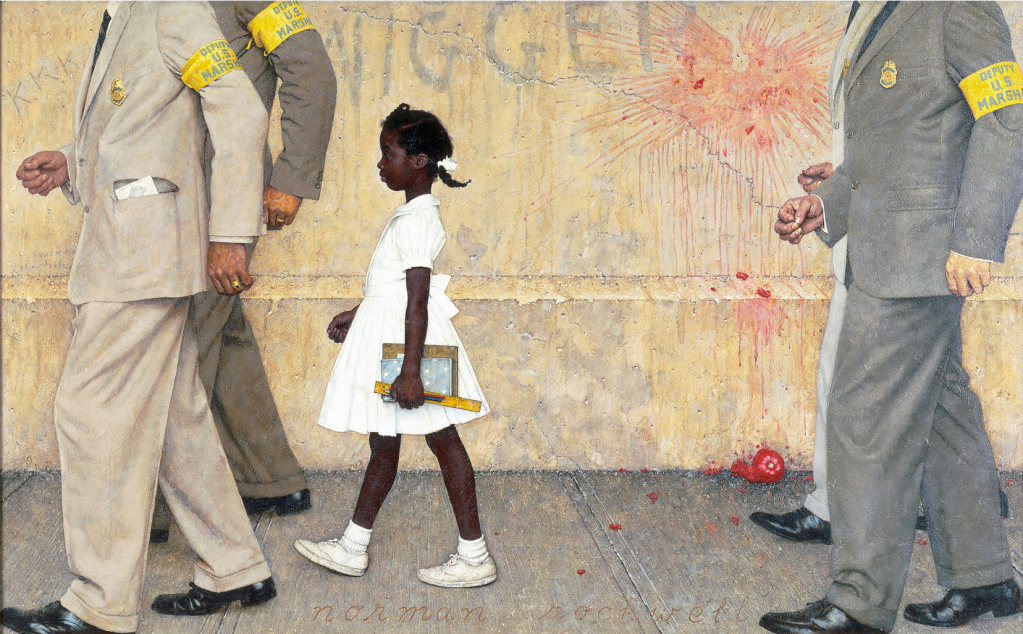

The Problem We All Live With, Norman Rockwell, 1963

The Problem We All Live With depicts a well-dressed and resolute little Black girl being escorted by four suited White men past a building with racist graffiti and a freshly-thrown tomato splattered on it. Guess what? Norman Rockwell, known for decades as an illustrator of nostalgic small-town, mid-century, warm-fuzzy “American dream” life for covers of The Saturday Evening Post, was actually bursting to address important social issues such as poverty and racism in his work, and he finally did so. He faced harsh criticism from people who insisted he should stick to safe, happy subjects, but he was undeterred. This painting was based on the day in 1960 when six-year-old Ruby Bridges had to be escorted to a newly-integated school in New Orleans by US Marshals to keep her safe as an angry White crowd screamed terrible things at her. Read more about it here.

Guernica, Pablo Picasso, 1937

Guernica is enormous–11 ft. tall, 25.6 ft. wide–all the better to consume you into its chaotic imagery of screaming people, a dead baby, a neighing horse, a bull, a room being invaded. Guess what? Picasso painted this as a reaction to the Nazis’ bombing of the Basque village of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, in their support of dictator Franco. Picasso was Spanish, and he was horrified when he learned of it. Guernica brought worldwide attention to the horrors of what was happening like nothing else had. While he was living in Nazi-occupied Paris during WWII, a German officer allegedly asked him, upon seeing a photo of Guernica in his apartment, “Did you do that?” Picasso responded, “No, you did.” Read more about it here.

The Third of May, 1808, Francisco Goya, 1814

The Third of May, 1808, is also huge–almost 8 ft. by 11 ft. A firing squad is killing unarmed men who are pleading for their lives as blood soaks the ground and dead bodies pile up. Guess what? Goya painted this in response to a horrific event. Napoleon had convinced the king of Spain, Charles IV, that his troops were just passing through on their way to conquer Portugal. It was a trick; instead, he installed his brother as the new king of Spain. On May 2, 1808, hundreds of Spaniards in Madrid rebelled. They were rounded up by Napoleon’s solders and massacred. Goya included Christian symbolism, such as the illuminated poor laborer in a crucifix-like pose with stigmata on his hands, whose submission to the faceless row of soldiers amplifies the inhumanity of the killing. It was recognized it as an anti-war statement and an admonishment of the public for being complicit in events that affect real people. Read more about it here.

The Death of Marat, Jacques-Louis Davíd, 1793

In The Death of Marat, a man has just been stabbed to death while writing a note in his bathtub, and his bloody, dead body is slumped toward the viewer. Guess what? Davíd was heavily involved in one of the most outspoken rebel factions of the French Revolution. So was his good friend Marat, a publisher. After Marat was murdered in his bath, unarmed and helpless, Davíd immortalized him and their cause by depicting him at death looking like Christ being taken down from the cross. Davíd and his entire club were later executed or imprisoned. Read more about it here.

Jackal biting lion, Unknown Egyptian artist, circa 1200 BC

This beautiful little sketch in ink on a hunk of limestone from the time of Ramses II was on display in the “Ramses the Great and the Gold of the Pharoahs” exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, as an example of drawings that artists made while learning. A jackal is biting a lion’s hind leg, and the immobilized lion is not happy. Guess what? According to the note next to it, historians have pointed out that this was a bold statement against the pharoah, because the lion was always symbolic of power and kingship, often representing the king himself. A lion would never be depicted this way in official Egyptian art. One wonders what prompted the “political cartoon” and whether the artist was punished for it! It proves that art has been used for political commentary for at least 3,000 years.

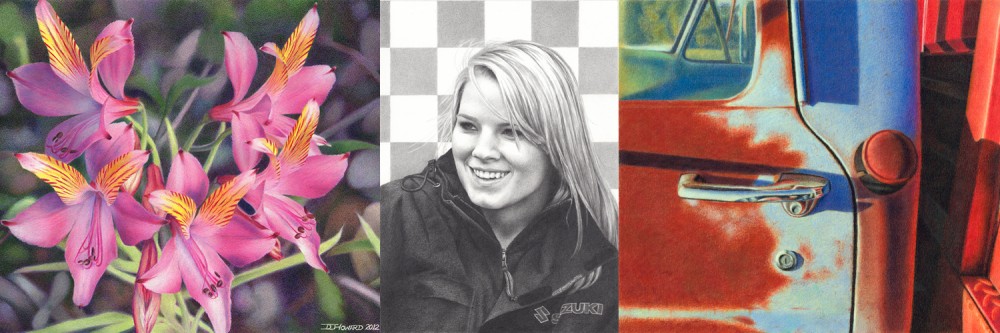

Zooming back to the present, why do I say “Someday I’ll probably offend you”? Because although I’ve created my fair share of “pretty pictures” and will make more because I like them, too, I also have a social/political conscience that tells me I should use my art to communicate about those issues as ideas emerge. There is no shortage of hot-button topics, and everyone has an opinion. Artists get to express theirs differently.

So far, my art in that direction has been on environmental themes like the human impact on monarch butterflies. That’s not especially controversial, but there are other environmental topics that are. That’s just as an example. Sooner or later I’ll no doubt express something in my art that someone–maybe you–will strongly object to, and will feel compelled to say so, and tell me what an idiot I am for expressing it.

Just don’t tell me “Go back to painting pretty pictures and stay away from politics. Politics doesn’t belong in art.” Because you’d be very wrong, as proved by more than 3,000 years of history. It’s something that art is especially good for.